|

|

|

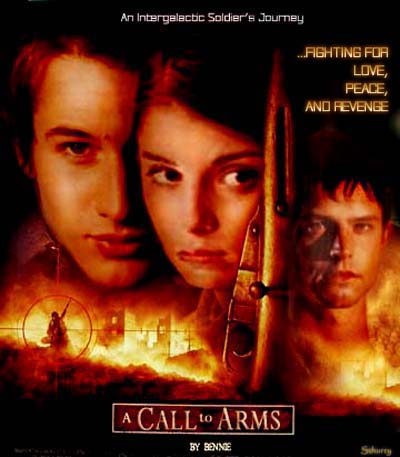

Author: Bennie

Banner by: schurry

Rating: PG13 for violence, language, and mature themes. Nothing too sexually graphic though.

Disclaimer: I own nothing Roswell.

Spoilers: It's a Futurefic, even borderline-AU, but I wasn't 'spoiled' so nothing in here anticipated any episodes past early S2.

Character Focus: Liz POV; CC

Author's Note: Thanks, Zoe, for coming up with a name for the enemy (I know it's just a coincidence it sounds like a combination of your brothers' names) and for insisting it stay CC. I think it works. And thanks, Reese, Sue, Angela, Deidre, Debbie, and everyone else who responded so nicely to this. You all totally went above and beyond. Oh, and the poems can be found here if needed: Dulce et decorum est and In Flanders Fields

This fic won Best Science Fiction Story and Best Future Fanfiction in RosDeirdre's Fall Roswellian Fanfiction Awards,

and Best Sci-Fi Fic in the Venus Rising Fan Fiction Awards.

Oh … god. God. I wish I could close my eyes and make it all go away.

Behind me, someone gags.

“Fuck me,” someone else says, softly, sounding broken.

I don’t turn around. I can’t move my feet. But I have something to say.

“No. Fuck them. Fuck them all."

I’m sure I’ve got everybody’s attention now, Human and Antarian alike. Careful, obedient, by-the-book Parker swearing? In another time and place, I’m sure it’d be prime gossip back at the barracks.

Right now, it’s a promise.

They have to pay for this, I decide, numb and barely comprehending the enormity of the massacre before us. A once vibrant form at my feet still oozes, one flat black eye staring blankly up at me, the other lost under greenish gore and the fine silvery hair of a young Antarian male. From the looks of things, he was fixing a child’s toy – maybe for a younger brother or sister? – when the attack came.

The thought echoes in my mind: they have to pay for this.

Then: I can make them pay for this.

The certainty of it fills me, gives me the strength to move. I step carefully over the body at my feet and walk towards the door.

“This ends. Now.”

My voice sounds flat. Machine-like. Without looking to see who falls in line behind me, I head for the door, stooping purposely on the way to lift a weapon off a dead soldier in passing. Poor kid. Never even got the chance to fire it.

The thought makes me feel old and … angry. Very angry.

A kid. Probably just out of training, judging by his – no, her crisp uniform. Higher Antarian, if the tattoo beneath one ear is any indication. I hope it’s a family crest, because I don’t think there’s enough of her face left to make an ID and Antarians don’t develop fingerprints the way humans do.

I hate the anonymity of KIAs like this, and the look on the faces of families and friends when they realize that they’re never going to know what happened to their sons and daughters and mothers and fathers and cousins and lovers and …

I’m beyond tears.

I want revenge.

As I make my way through deeply rutted ravines and tangled fields and strange-smelling forests, I distract myself with thoughts of my own childhood.I remember studying Earth history, memorizing places and dates and treaties and precipitating factors, but I never really knew what war was until I traveled light-years from my home to fight in one.

It seems like another lifetime, and in a way, it was. I was supposed to die before Earth found out there was other life in the universe, friendly life but also covetous life, life that understood the colonial impulse all too well. Life that saw Earth’s abundant water supply and resented it along with the Antarian royalty it unknowingly harbored.

Not that Humans are much better. I know this, I do, and for years I’ve struggled to explain to my curious Antarian friends why I fight to protect and defend a planet so deeply divided and self-destructive when I call Antar home now.

Hell, I struggle to explain it to myself. Humans are petty. We are base and cruel and unenlightened and unwilling to compromise. But … we have poetry.

It may not seem like much, but I hold on to that. Apparently poetry is not a step all cultures go through; Antarians, for instance, pretty much went from forming entire sentences straight to telepathy. Earthlings, on the other hand, developed a higher level of DNA stability and a slower mutational pattern. So we’ve had the time in our latest evolutionary plateau to develop formalized, structured, ambiguous language. And there’s significance in that.

I believe this. Maybe more than I believe in just about anything.

Poetry. I may not understand exactly what it means half the time, and frankly, I think most of it sucks, but I know it’s important just because it is. Because it endures, a testament of humanity that no one can take away from us like they’re trying to take our planet.

In my childhood, before I knew what war really was, I had to write a paper comparing two wartime poems. I chose In Flanders Fields and Dulce et Decorum Est because my teacher recommended them and they were short. I wasn’t expecting much, maybe some crude rhymes about pain and death.

Pain and death – yes. Crude? No way. I must have read those two poems a hundred times, silently and out loud, trying to understand how descriptions of places I’d never see, of people I’d never meet, of events I’d never be a part of, could affect me so profoundly.

Like now. Those poems gain meaning for me even as I look at the slack faces around me, at the masks giving lifeless corpses identity, reminding me that I’ve played cards with that one and shared a berth with that one.

Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori: It’s sweet and fitting to die for the fatherland.

In other words, there’s no greater honor than to die for your country – or your planet, or your solar system. I do believe this, actually, but I also hear the bitterness in these words, feel the pain and despair that prompted the sharing of them by a soldier who was barely more than a boy himself when he wrote them.

At times like this, those words achieve talisman-like quality.

And I’m deluged with thoughts of destruction. It’s all around me, and part of me is amazed and distressed that I want to create more. More destruction, more carnage, more dead bodies for loved ones to weep over, to plant memorials and flowers (maybe even poppies) for, to compose words of mourning in honor of.

But I do.

And I will.

There’s a certain poetic irony to that, I think.

Miles away, outside an enemy camp, I need no words to convey what I want.

The hand signals are second nature now, which is useful when the dust is so thick or the enemy is so near that opening your mouth is dangerous. And if there’s one thing every race here has in common, it’s the tapering multi-jointed digits extruding from the end of our upper limbs. Two knuckles or three, we can all speak the same language when we need to.

We’ve been tracking this band of Trejantisian raiders for some time now, but we were waiting for orders to strike. Our officer in charge, Lieutenant Hothe, is a cautious man and he’s been waiting for some indisputable proof that they were the ones tearing up this distant corner of the Antarian Empire before issuing any orders.

Screw that, and screw Hothe. I don’t need any more than what every ounce of battle-trained intuition is telling me, that these are the ones. And I’m not waiting to find more “proof”.

About twenty soldiers followed me here and are watching my hands as I sketch out a basic strategy. Some of them outrank me, but not by much and none question me. We can work that crap out later. Right now I don’t care about any of it. No, all I care about is the twenty-five or so Trejantisian officers we found in that building over there.

I know they’re officers because they still have that look, the one that says they think they’re getting out of this war alive and with money in their pockets. Human, Antarian, Trejantisian, any of the myriad other alien species tangled up in this interplanetary war - we’re all the same. We all have hierarchies and those hierarchies have elites.

There are ordinary soldiers too, but they’re outside. They’re rolling their eyes and mocking their superiors, and I’m not so far gone that I’m going to kill them in cold blood.

At my signal we release low-power charges among them, silent blasts of directional sonic force to knock them out with a minimum of fuss. As far as weapons go, they’re expensive and difficult to re-stock, so we have to use them sparingly. They’re actually designed for taking prisoners. But today is not really about taking prisoners. Today … today is about revenge.

And I want the animals we’re here to destroy fully conscious and armed when we attack. I can’t do what I want to them if they’re prisoners and protected by protocols and war conventions and my own conscience.

I’m in the doorway now, looking in. None of them see me yet. None of them see the look on my face as I watch them compare the spoils of their last crusade, no doubt the one that wiped out the agrarian settlement we just left.

One Trejie idly fingers a neckpiece of local design, and I want to shove it down her throat.

One thing about aliens and alien powers: you don’t get idiotic ideas about leaving women behind when they can crush the enemy with a raised hand and a moment’s concentration. Humans have been a little slower on the uptake, but not by much. Not since human leaders discovered that human females are more likely than males to develop new talents through contact with Antarians.

Take me. A couple healings, a few connections and a little alien sex as a still-developing teenager, and I can project an image so real you’d swear it was a mind-warp. It’s more like a hologram, though. No mental intrusion. Makes giving reports a lot easier, I tell you, and know that Kyle was jealous as hell about it. If I wanted, I could sneak us all in here before they think to trust their ears and their noses and ignore their traitorous eyes. They’d be sitting ducks.

But I don’t want to use any tricks now. I want them to see their death coming. I want to see them hurt. I want to see the looks on their faces when we kill them.

And we will kill them.

One has just looked up, and I know he’s seen me because he freezes mid-gesture.

Taking advantage of his hesitancy – he can see how short I am, I figure, and he’s wondering if I’m a child – I raise my weapon and fire.

He falls back, an energy burn sizzling on one temple.

There is silence for a moment, until one of his companions speaks to us in a language neither Earth-based nor Antarian. I don’t understand his words, but he’s dressed a little too well to be a raider and seems to be pleading. It makes me angry. I don’t want to give him the chance to talk his way out of this.

He and his companions didn’t listen to the pleas of the children they slaughtered, did they?

“Not a fucking chance,” I whisper, and all hell breaks loose.

Our official squadron motto is “Honor above all.”But according to Antarian tradition, we enlisted have our own rituals that bind us together, and one of them involved devising our own mission statement. So when the strategists fade back, when it’s just us in hostile terrain and facing the enemy, that is what you’ll hear us muttering under our breath, or mouthing the words.

Translated, our spirit, the spirit of my platoon, is tied up in three phrases: War is death. I am at war. Therefore, I am death.

It sounds a lot more impressive in the original Antarian, and one day I hope I can pronounce the words properly. But even in English they serve their purpose. They focus our attention, sharpen our focus, harden our will.

We are unified in death.

A lot of times, battles are won before the soldiers ever hit the lines. Supplies, resource allocation, value and worth of the target – they’re all determined in back rooms, by generals and accountants. When you’re strategizing, when you’re playing with people’s lives and expensive toys, you aim for minimal contact and minimal loss. Whoever plays the game best, wins.

Kyle was always good at that part of it. He liked machines, liked being able to distance soldiers as far away as possible from the battlefield or at least shield them as much as possible on it. He looked forward to being one of the guys at the planning tables one day, to dealing with facts and figures rather than bodies.

Me, I think it’s important to see the effects of the decisions you make firsthand. I say you need to look your enemy in the eyes and remember why you’re doing this. You need to remember that lives are being lost, not numbers, and that real people – allies and enemies alike – are suffering and dying for survival. Not just some blips on a screen.

Oh, I’m not an idiot, and I don’t really have a death wish. I don’t enjoy the rush of nausea and uncertainty and fear that leaves me trembling before and after every confrontation. And I do think before diving in. I think about how to end it quickly and efficiently because I don’t want to lose people if I don’t have to. Not pawns, people. I think about the orders I am given, and I weigh them against my own instincts because if something goes badly I like knowing I have options.

Like, one time I was second in a small party sent out to scope a likely looking spot for ambush. We found one, and got separated in the following skirmish. I ended up alone, low on ammunition, and faced with this huge and wily-looking Trejantisian who’d come after me. My training told me to retreat using gunfire to discourage pursuit, maybe project a distraction of some kind, but it occurred to me (and not for the first time) that height could be a disadvantage too. So, with a little luck and a lot of dodging one way or another, I closed in on him and grabbed at the incendiaries I’d noticed at his belt. Then I dropped and rolled away, and whoosh! He was toast, and I hadn’t wasted any of my own ammunition or psychic energy to do it. Heading back, I had ample time to snipe-hit the rest of the ambush party who were too busy fighting my group to pinpoint where I was in the treetops overhead.

I got a medal for that. It’s gathering dust in a drawer somewhere.

Now I use a similar duck and roll maneuver to slide in under cover of chaos, stabbing when I can and throwing tightly focused beams that remind me of the laser pointers my high school teachers were so proud of.

It’s over in minutes. Maybe seconds; it’s hard to tell. But it does end, and we prevail. I get in two more kills myself.

It doesn’t help, of course. It’ll never bring back the girl with her face blown off in the town we just left, the child whose weapon I just used to sear a hole through some Trejie’s chest.

But I’d do it again. And I probably will.

War is death. We are at war. I am death.

Afterwards I gather my troops back at camp.I look to Lieutenant Hothe as if for instructions, but he isn’t fooled. He’d been injured a day earlier, and only just limps out of the medics’ tent in time for our return from the impromptu raid. Looking directly at me, he tilts his head and waits for me to speak. My future will depend on what I do in the next few seconds.

Hell, the futures of all the people around me may well depend on what happens in the next few seconds. The circumstances might have different, but I’ve lived this moment before, and I’d recognize the feel of fatalism a mile away.

This man has the power to execute me on the spot, if he decides I’m a danger to the platoon and the cause. Then he could prosecute those who followed me for mutiny. But I've served with Hothe for some time now, and I can read him a little. Right now, I think the regret in his eyes might be for the leg injuries that kept him from following me to the Trejie camp too.

Regardless, I won’t make excuses, and I will never apologize for what I did this day.

“Good fight.” It's an ancient Antarian military greeting from eons ago that lives on in myth and legend and tradition.

There are nods around me, as Antarians and humans alike hear what I am saying as well as what I am not. We are fighting the good fight. And we can never forget why we are fighting, who we are fighting for, who we are fighting against. Sometimes, I know, vengeance is justified.

And speeches are overrated.

“Perhaps we should dispose and regroup,” I suggest respectfully, though no one’s fooled by my show of humility. “We could head back tomorrow.” A full week earlier than planned, actually, since there’s nothing keeping us here anymore and we need to debrief and ship out to somewhere else.

No one argues. Hothe simply nods.

A beat later and we scatter, using scanners to record the images, DNA patterns, and hopefully the identities of the dead before vaporizing their corpses. When we are done, we will meet back at the other site to do the same there.

It doesn’t happen until we’re on the move. When no one’s looking, Hothe steps beside me, adjusting his gait to match mine. Damn short legs, I always feel like I’m scurrying, especially next to these willowy Antarians. But we’ve learned the hard way that we have to get regular exercise to stay alert and focused, so when we can, we slow down the transports so some of us can get out and walk for a while.“I’m going to have to report this, you know.”

I know.

He continues as if I’d said it aloud, his tone hard. “Parker, I can’t decide whether you deserve a promotion or a court-martial. And if you think your status in court will affect my decision, you’re kidding yourself.”

I don’t answer but I’m listening to every nuance of his tone. He means every word.

“You don’t have anything to say for yourself?”

I’m not looking at him; my head is sweeping back and forth in my best field lookout manner. It’s second nature now. But when my head tilts his way, I sneak quick, sideways glances at his profile.

“There’s an old Earth saying,” I comment quietly, my voice hoarse but even. “Actions speak louder than words.”

We walk our road in silence, marching in step but lost in our own thoughts.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18